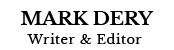

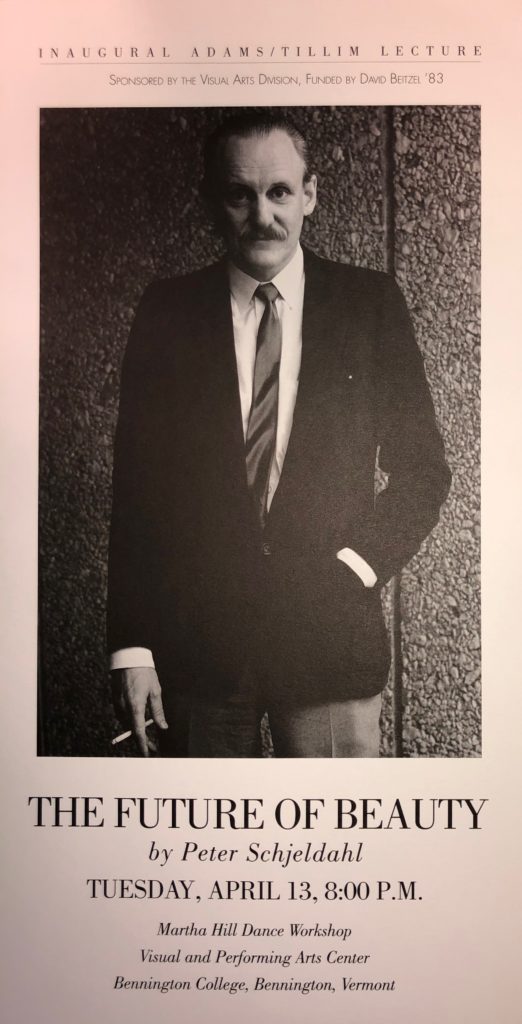

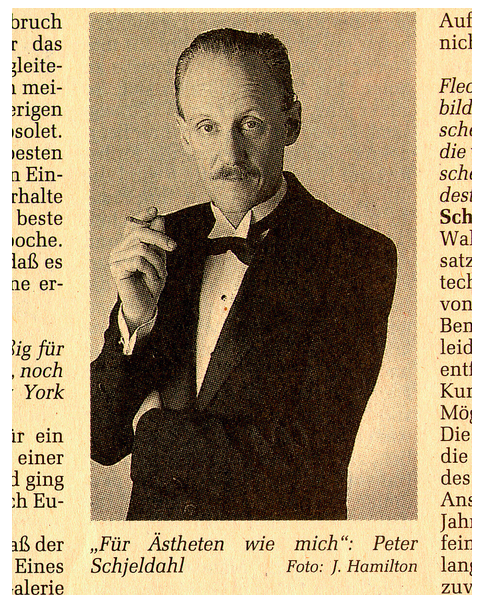

When Peter Schjeldahl’s doctor handed him a diagnosis, in 2019, of Stage 4 lung cancer, the New Yorker art critic did what writers do: turned life into art, writing a discursive yet seamlessly joined essay, 9,000-plus words long, tracing the arc of his life (he was 77 at the time) and confronting a mortality just around the bend.

In “The Art of Dying,” Schjeldahl mines the absurdities of a generically dysfunctional 1950’s childhood for droll humor: “In love letters, my mother addressed [my father] as the President, and he called her the Student Body.” He tosses off hardboiled witticisms that split the difference between Oscar Wilde and Raymond Chandler (both of whom he admires; the essay’s title riffs on Wilde’s “Art of Lying”). “Quit now?” he says, of his refusal to kick the habit that wrote his death warrant. “Sure, and have the rest of my life be a tragicomedy of nicotine withdrawal.”

He tried to write a memoir once and failed, he tells us, because he doesn’t “feel interesting” to himself, and because he doesn’t trust his memories “(or anyone’s memories) as reliable records of anything–and I have a fear of lying.” But the death sentence sets him free. He comes clean about the insufferable arrogance of his younger self, his willful cruelties, the crash-and-burn nadir of the alcoholism he finally beat. “I am beset,” he confides, “by obsessively remembered thudding guilts and scalding shames.”

Right on cue, Susan Sontag puts in an appearance, inflicting ritual humiliation on our narrator at a party. (Sontag could, by all accounts, be a monster of snobbery.) But her influence is felt throughout the essay, too, partly because Illness as Metaphor is an unavoidable landmark on the cancer-memoir landscape, partly because “Notes on Camp,” whose musings circle her theme rather than marching to a conclusion, is the model for “The Art of Dying.”

Near the end, Schjeldahl plays footsie under the table with God, toying with belief, dismissing unbelief as “a pleasure for adolescent brains with energy to spare.” It’s reassuring to know he hasn’t checked the old arrogance at death’s door, but there’s a lesson here for writers: never presume upon your reader’s sympathies; they can shift with the wind, as mine did, reading this flip dismissal. The creationist homily at the end of an otherwise bracingly bullshit-free essay set my teeth on edge: “The fact of our existence suggests a cosmic approval of it.” Well, either that, or the vagaries of evolution, this implacable old atheist thought, squirming in his pew.

Still, there’s much here for anyone in search of wisdom about the writer’s craft and the writing life from a master of the critical essay and consummate stylist. Critics will prick up their ears at the insights he offers into his philosophy of criticism, which owes an acknowledged debt to Wilde and Baudelaire. “When I was young, I had personal and coterie loyalties,” he writes. “Then I decided to see how responsible a critic I could be, open to ideas but never prescriptive or proscriptive. By academic measure, this makes me not a true critic at all. I can live with that.”

Elsewhere, Schjeldahl has said that his essays aren’t so much reviews–thumbs up, thumbs down–as responses; they’re less about the work he’s looking at than his reaction to it. It’s a distinction that’s more timely than ever in a culture where the quantification of everything has turned criticism into service journalism (“Rotten Tomatoes, home of the Tomatometer, …the most trusted measurement of quality for Movies & TV”), so much so that the film critic A.S. Hamrah strives, in his work, for Tomatometer-proof criticism. “Write so that Rotten Tomatoes cannot apprehend your work,” he counsels, in his collection The Earth Dies Streaming, “which will allow its meaning to be deformed to the point where studios will not know what to do with it.”

Here are a few clip-and-save insights from “The Art of Dying.”

Journalism used to be a stern and salubrious discipline that taught generations of newbies to cut the crap: “I acquired the most useful writing discipline of my life from fat, cigar-chewing Jersey Journal copy editors–burned-out reporters–at desks in a half circle facing the city editor. With No. 1 pencils, like black crayons, they’d eviscerate my copy. I’d rewrite, and they’d do it again. Finally, they sent it down to the Linotype–the old racketing, reeking contraption for setting type from molten lead. Those men still sit by as I write, pencils in their itching paws.”

The dwindling number of publications that still edit, really edit, their writers coupled with the rise of self-publishing platforms like Thought Catalog and Forbes.com, whose clickbait-y “user-generated content” is never desecrated by a No. 1 pencil, is depriving generations of writers of the boot-camp basic training Schjeldahl and legions like him got.

Search out publications with editors who’ll give your precious prose a buzz cut with a chainsaw. If you can’t find any who will have you, hire a freelance editor to run one of your best pieces through the bullshit detector. Take that line-by-line critique to heart, internalizing what rings true, no matter how painful. As you write, imagine one of Schjeldahl’s Damon Runyunesque cigar-chompers looking on, eager to kill your darlings with a mercy stroke. Beat him to it.

The shadow of hardboiled fiction and Hollywood noir still shapes the American voice (at least if you’re a white guy of a certain age). Everything about that paragraph I just quoted reeks of Raymond Chandler, the poet laureate of mean streets: the cynical newsies; locutions like “paws.” “Raymond Chandler proved that the American form of Montaigne-grade aphorism is the wisecrack,” says Schjeldahl, in an essay punctuated by deadpan zingers. “Wisecracks in Chandler are existential rescues of imperiled self-possession. Worth the risk to the detective of a punch in the gut. And conserving calm for noticing the world.”

Chandler’s pulp-magazine sexism, sneering homophobia, and brazen racism will be dealbreakers for some, but if you can get past them, read his short stories for their mastery of the American idiom, with its hard-edged clarity and wiseacre patter, full of ricocheting one-liners.

Tropes–the similes and metaphors that make Chandler’s writing swing–seem to be falling into disuse among younger writers who came of age in the social-media era. (Why, exactly? That’s the stuff of another column.) Popular prose is the poorer for it. A writer’s attitude comes through in his or her tone and persona, and nothing conveys either like a figure of speech. ”Closeness is impossible between an artist and a critic,” writes Schjeldahl. “Each wants from the other something…that belongs strictly to the audiences for their respective work. It’s like two vacuum cleaners sucking at each other.” Chandler could’ve written that last line. Or these: “…stretching out the last word to sound like something nasty going through a mangle”; “…ego dissolving like Alka-Seltzer in warm water.” Figurative language performs the conjuring trick of turning words into images, a miracle I never get over.

“Writing Consumes Writers”: “The passion hurts relationships. I think off and on about people I love, but I think about writing all the time.” “I broke free [of his family] at the cost of hating myself for letting my siblings down. … [P]eople I know will roll their eyes–same old Peter!–at how little of their deserved shrift they’re receiving from me here as, alone, I linger again with my lifelong lover: you, reader.”

Schjeldahl’s oncologist gave him six months to live, so why is his byline back on the New Yorker marquee? Reportedly, his cancer’s in remission. Does that deflate the currency of his self-eulogization, make it somehow less affecting? Not to this reader. The chaplain and the screw came for the writer in his cell, then he got a stay of execution. Now he’s got to live with the altered perception that comes from seeing your death mask in the shaving mirror. Will it change how he sees the world, looks at art, writes about it? How can it not?

In “The Art of Dying,” Schjeldahl quotes Samuel Johnson: “When a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.” Try a thought experiment: write a eulogy for yourself, a string of stock-taking vignettes modeled on Schjeldahl’s seemingly (but only seemingly) free-associated ruminations.

Too forced? Then just write as if you’re living on borrowed time. Because you are.

Afterthoughts

Schjeldahl’s style not to your liking? Other exemplars of the parting-thoughts-at-death’s-door genre include “My Own Life” by Oliver Sacks and “Topic of Cancer” by Christopher Hitchens. Robert Krulwich, co-host of the WNYC show Radiolab, wrote a thought-provoking little essay on the genre, touching on Montaigne, Tolstoy, and the poet Mark Doty, all of whom squared their shoulders and stared death in the eye.

A word from our sponsor

Need seasoned editorial help with your premature eulogy–or, for that matter, your manuscript-in-progress? A sounding board for a project that’s still just a gleam in your eye? Coaching to take your writing to the next level? I’d love to help you realize your vision. Visit my editorial and coaching site.