As an author who’s seen the fruit of seven years’ labor reduced to a smoking hole by a drone strike in The New York Times Book Review, I sometimes wonder why there aren’t more revenge killings by aggrieved authors.

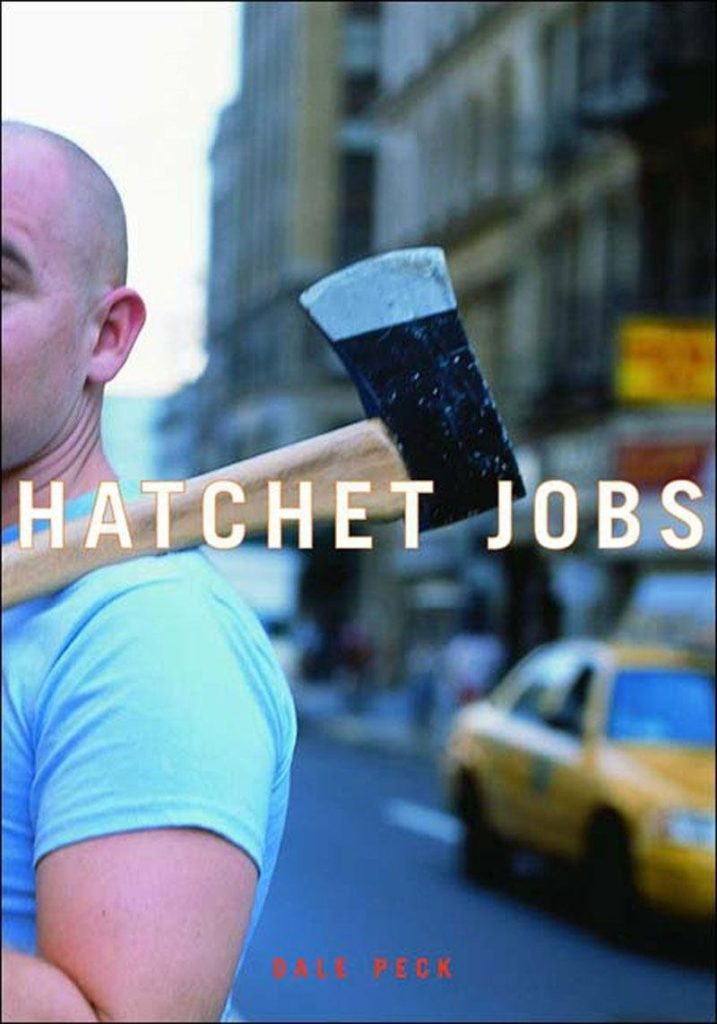

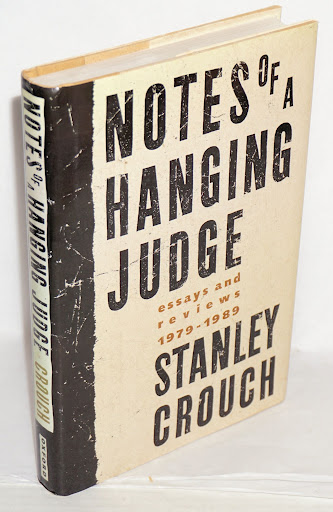

Come to think of it, I can’t recall any, which, given the nursed grudges and preening egoism of the Lilliput of Letters, is nothing short of miraculous. The pugnacious jazz critic Stanley Crouch once “pimp-slapped”–backhanded–the book reviewer Dale Peck, while Peck was lunching in a West Village bistro, for the crime of pouring scorn on his novel Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome. If he ever panned him again, the hulking Crouch told the smaller man, “you’ll get much worse.” It was an ugly thing, made uglier by the fact that Peck is gay and Crouch, a reactionary who never scrupled at homophobic slurs, once derided him in Salon as “a troubled queen” and told James Atlas, in the New York Times Magazine, that “bitchiness is [Peck’s] version of macho.”

Perhaps because he was a barrel-chested brawler who bought into the Hemingway myth of the writer as (figurative and literal) pugilist; maybe because he was a contrarian Black intellectual with no fucks to give about the overwhelmingly white critical establishment, or even about other African-American critics like his Village Voice colleague Harry Allen (whom he clamped in a neck-twisting wrestling hold called a cobra clutch, prompting his firing), Crouch was applauded by some as echt gangsta.

“Crouch has a taste for swinging that is nothing short of a variation on the ‘I ain’t no punk’ theme seemingly encoded on the DNA of all black males,” Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote, in his Village Voice appreciation, “Crouching Stanley, Hidden Gangsta.”

“I have a kind of Mailer-esque reaction to the way some people view writers,” Crouch once told The New Yorker. “I want them to know that just because I write doesn’t mean I can’t also fight.” … “People perceive writers as being soft and not assertive. And there is a legacy of writers, going back to Hemingway, asserting their masculinity in an overt way,” says [former Voice writer Nelson] George. … Crouch’s street mojo also adds another layer of mystique, particularly for his white fans.

[N]ever let it be said that he who purports to be a black male gives up the beast. That it’s all an act, and he really won’t kick your ass. That in the middle of politicking over Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and tea, he won’t go David Banner, upturn your table of crumpets and coffee-cake, grab you by the collar, drag you out into the darkest alley, and show you that, yes, what you have heard is true. That he will not swing through on his dick and snatch your Jane on a vine like Tarzan. Never let it be said that Jim Brown was not the essence of him. Never let it be said that he–whether Crip or Crouch–failed to be a nigga.

There’s a lot to unpack here, and it has to be unpacked with the meticulousness of a bomb squad defusing an IED. That’s beyond the scope of this essay and way above my pay grade, as a white writer of the soft-boy, crumpet-dunking persuasion.

I will note that Crouch’s tendency to “assert his masculinity in an overt way” has to be seen, as Coates implies, in the context of the (figurative and literal) emasculation Black men have had to endure, on these shores, for nigh on four centuries. But I’ll also point out the rancid “no homo” subtext of the “’I ain’t no punk’ theme,” and of the association of writers with wussiness (“being soft and not assertive”). (In the psychopathology of everyday life in the U.S.A., anti-intellectualism often presents as misogyny or homophobia.) As for the bit about “swing[ing] through on his dick and snatch[ing] your Jane on a vine like Tarzan,” I’m not going anywhere near that, though I will say I wish Coates had teased out the uncomfortable implications of white fans consuming Black “street mojo.”

Crouch’s bad behavior should’ve made him an overnight pariah, but Peck’s gratuitously snide, cuttingly personal style has made him universally unloved, a scorpion stung to death, socially, by his own tail. “According to Mr. Crouch, calls and letters of congratulations have been flooding in, praising his non-verbal approach,” the New York Observer reported. “’I knew this guy was disliked, but I had no idea how disliked,’ he said.”

That Peck is a gratuitously ad-hominem hit man, and that his long and gleeful list of enemies applauded his comeuppance, shouldn’t matter. Violence is the first refuge of the unwitty and the witless. It’s especially despicable if the bully is a writer, a boot in the face of everything writers and writing are supposed to stand for. When Norman Mailer punched Gore Vidal at a cocktail party, Vidal, whose flick-knife wit always made short work of Mailer’s truculent bluster, was supposed to have quipped, “Once again, words fail Norman Mailer.” Slapping a reviewer or socking a literary rival isn’t just thuggishness; it’s an assault on the life of the mind, not to mention a tacit admission of intellectual defeat. Of course, that doesn’t mean most writers haven’t consoled themselves, after a critical drubbing, with fantasies of bludgeoning the reviewer to death with a hardbound copy of the offending title and burying him or her alongside Joe Pesci in that cornfield in Casino. I know I have.

On the July 29 episode of the podcast Fiction/Non/Fiction, co-host V.V. Ganeshananthan asked the Slate book critic Laura Miller whether she gives much thought to potential backlash from writers whose books she’s buzzsawed. “I wonder, when you write something negative,” she said, “do you worry that the writer is going to get mad?”

Miller’s thoughts on the question are sage counsel for any writer who’s ever been on the receiving end of a hatchet job and finds herself searching Craig’s List for contract killers.

- “Most authors may have the urge to respond to a negative review, but usually their publicists stop them; it’s considered to be really bad form, and then it just becomes a spectacle for a jeering mob to be entertained by. Alain de Botton did that when a critic named Caleb Crain negatively reviewed one of his more recent books. He sent a lot of nasty e-mails and nasty tweets at Caleb, and as a result, he looked like a fool.”

- “I wrote something [for Salon] about a Caleb Carr book, a negative review, and he just totally flipped out and sent these long letters to Salon denouncing me, full of insults and high dudgeon, and the editor of Salon was thrilled and published all of them. … He just lost his temper, and he didn’t have a publicist who could control him. … It’s not a good look for most authors to make that move, and the fact that publications are just thrilled to publish it should be an indication that they’re not getting their point across.”

- “The one case in which someone has every right to respond, to be angry, is if the reviewer gets a point of fact wrong. This is particularly true…if you accuse someone of getting a fact wrong and you are, in fact, wrong. Then that author should write in and correct that and … the critic should apologize and the publication should post a correction.”

Gospel truth. Every writer who responds to a critical pan with a blast of invective is confident he’s just knocked some popinjay off his perch. And every writer who thinks that is wrong: wit depends on an aloof, self-amused cool, a near-impossible state to achieve when you’ve been driven into a homicidal rage by a rotten review. You can’t not take it personally, and the bleating of your wounded ego will come through, loud and clear. Not convinced you couldn’t give as good as you got? Watch the self-immolation of a petulant, drink-sodden Mailer on the Dick Cavett Show, trying to pimp-slap the coolly disdainful Vidal for his skewering of Mailer’s anti-feminist screed, The Prisoner of Sex (a project not helped by Mailer’s admission, at one point, that he stabbed his wife). Then ask yourself: if Mailer couldn’t pull it off, can you?

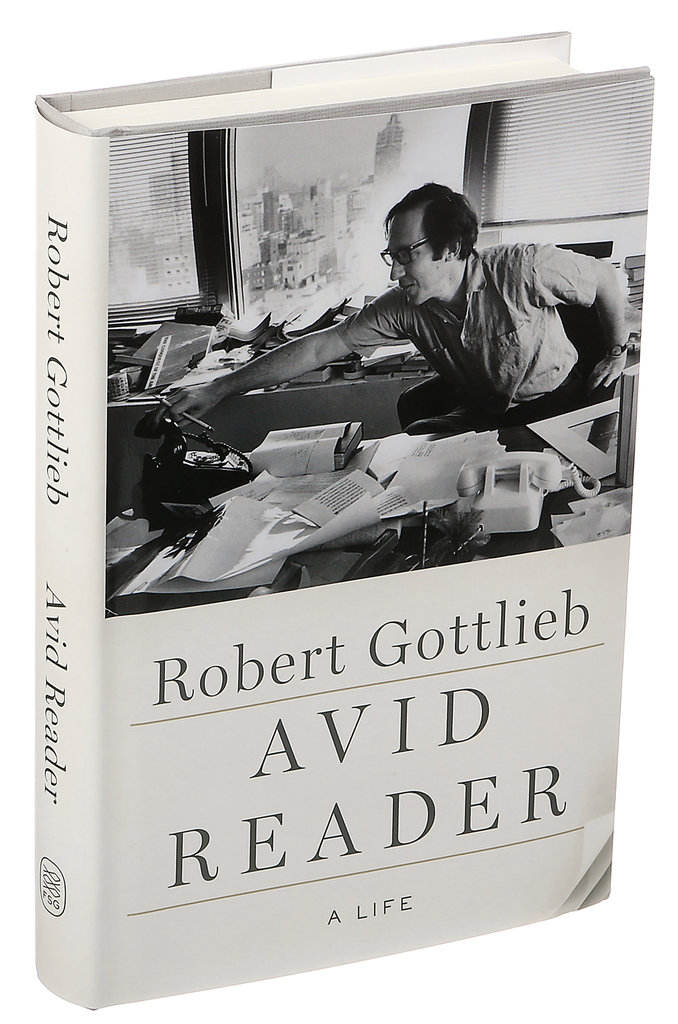

When I opened the New York Times Book Review to discover that the legendary editor Robert Gottlieb, a storied figure in New York publishing, had stooped to conquer my biography of Edward Gorey–at 4,000-plus-word length, no less–I had to be restrained from purchasing a sniper’s rifle.

My editor suggested I sleep on it and see if I felt the same brain-boiling fury the morning after. If I absolutely had to respond, he advised, I should confine myself to the facts. “The more matter of fact your tone, the more damning the response will be.” (Tone is everything, on the battlefield of writer’s feuds; see Mailer v. Vidal.) The head of publicity offered her wisdom, too, cautioning me that “rebuttal letters to the editor can sometimes draw more attention to a negative issue than right a wrong in terms of public awareness and perception. Readers can see it as upset at criticism no matter the real facts of the matter or merits of the case.”

Breaking with the habit of a lifetime, I heeded their advice and held my fire–a smart move, in retrospect. Gottlieb, who’s been in the game since 1955, was editor in chief at Simon & Schuster and Knopf. He’s edited Toni Morrison, John Cheever, Doris Lessing, Robert Caro, and John le Carré, to name just a few. Oh, and he discovered Joseph Heller and edited Catch-22. Going up against a literary mandarin with the cocktail-party capital he’s amassed is reputational seppuku. Better to place your faith in the wise reader, hoping he or she will make your case for you, as some in the Times comment section did. “I can’t wait for the NYT’s review of Mr. Gottlieb’s review,” wrote one ironist. “May it be as charitable to him as he is to Mr. Dery.” Readers rose to the occasion, cataloguing the inaccuracies in a review that “takes [Dery] to task for inaccuracies”; lamenting that “much of the review comes off as a surprisingly sad attempt to…enhance his own cultural bona fides”; deploring the reviewer’s tone as “overtly hostile…as though [he] felt threatened by Dery.” One wag won the thread: “I left this review thinking that Gottlieb really loves Gottlieb. And Balanchine. And Gorey. In that order. Dery not so much.”

Balm to the badly stung. Still, a spectacularly nasty review can scar a writer for life, and old injuries, like Dr. Watson’s bullet wound in the Sherlock Holmes stories, can “ache wearily at every change of the weather,” though in the writing life it’s emotional weather. New pans, if they touch on points familiar from earlier hit jobs, can reopen old wounds. “How many great talents have been rendered mute and inglorious,” write the editors of Rotten Reviews & Rejections, because reviewers sneered them into silence? Melville was met with a blizzard of derision, they remind us–and put aside his pen for 40 years.

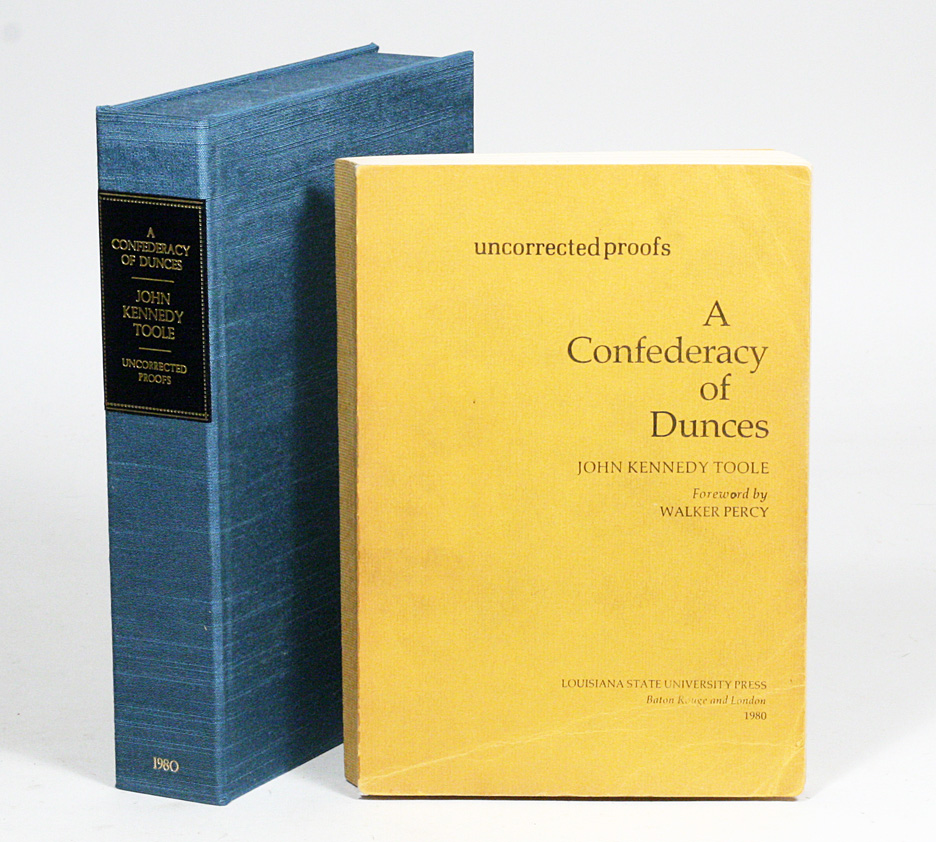

And then there’s John Kennedy Toole, whose novel A Confederacy of Dunces was rejected so many times he spiraled into a pitch-black depression and committed suicide at 31. One of the editors who didn’t get Toole’s novel was a book-publishing wunderkind named Robert Gottlieb. By contrast, the novelist Walker Percy got it, and after three years of dogged advocacy, found a home for it. The version published was Toole’s first draft, the one Gottlieb rejected, with no substantial revisions. It was greeted with a chorus of critical acclaim. A year after its publication, Toole was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. In the sleepless watches of the night, I’m consoled by Toole’s posthumous revenge–and Gottlieb’s eternal chagrin.