Stuck on fast forward, we’ve accelerated to the point where our multitasking, instant-messaging speed tribes are experiencing an eerie nostalgia for the present—an ironic world-view in which every experience is framed in air quotes.

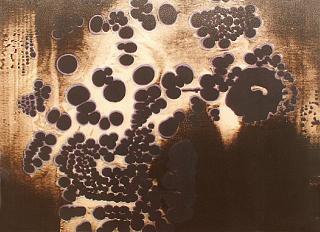

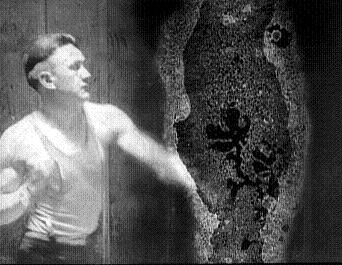

Still from Decasia: The State of Decay (Bill Morrison, 2002). Courtesy Decasia website.

(The following is excerpted from the lecture I delivered at Cabinet magazine’s “Nostalgia” conference, in Mexico City. If Cabinet decides to publish an anthology of papers from that conference, as Editor Sina Najafi has hinted it might, a radically revised, substantially expanded version of my lecture will presumably be included in it.)

“Obsolescence confers instant bygone status,” writes David Lowenthal, in The Past is a Foreign Country. He quotes Bevis Hillier, who believed that “‘history was being recycled as nostalgia almost as soon as it happened.'”

The psychological state I’ve called “nostalgia for the present” is a close cousin to the anticipatory nostalgia experienced by the character in the Margaret Drabble novel Jerusalem the Golden who savors “a honeysuckle-filtered, sunny conversational afternoon” because she knows she’ll savor it all the more, in years to come, as the source of “the most sad and exquisite nostalgia.” Writes Drabble, “She was sad in advance, yet at the same time all the happier…for knowing that…she was creating for herself a past.”

But our nostalgia for the present is more melancholy than Drabble’s, shadowed by the inescapable feeling that, at a time when styles, trends, and media phenomena seem to spring up, wither away, and decay at time-lapse speed, everything around us is already “history.”

Still from Decasia: The State of Decay (Bill Morrison, 2002). Courtesy Decasia website.

The endpoint of this existential perspective is the feeling that we’re living in an archaeological dig, a museum diorama. Looking at our appliances, we’re able to foresee the moment, not far from now, when they’re quaintly out-of-date, like the bulbous toasters and heavy, enameled mixers of the 1940s that inspired Michael Graves’s retro-cute housewares for Target. And, if we squint hard enough, we’re able to see our labor-saving gadgets as ancient artifacts, which, thanks to the giddy runaway of technological innovation (urged along by the market-driven doctrine of style obsolescence), they almost instantly are. (Of course, in the culture where fads, fashions, intellectual trends, and even people are consigned to the dustbin of history with the sardonic expression, “That is so last five minutes,” antiquity is a relative concept.)

Nothing captures this sense of living in a ghost world better than Bill Morrison’s elegiac movie Decasia: The State of Decay (2002), a jittery dance of death collaged from decomposing nitrate film stock taken from movie archives all over America. Utterly unlike anything you’ve ever seen, Decasia is a tone poem on the theme of decomposition—what the Victorian photographer William H. Fox Talbot called “the injuries of time.” As the flickering of the sprocket holes keeps visual time along the film’s edge, blobs boil across the scene. Holes gape in mid-screen, devouring the faces of smiling people. If you’re inclined to Rorshach blots, you can see ectoplasm, amoebas, suppurating wounds, or intergalactic wormholes in these patches of disintegrating celluloid. The footage is old, older than time, salvaged from antique travelogues and melodramas and industrial films. Dervishes whirl in a blizzard of pocks and scratches. Rocket cars orbit a ride at Coney Island’s Luna Park, vanishing into a roiling mass, then reemerging intact, then vanishing again, endlessly. A couple embraces and dissolves into each other, like mannequin lovers in a wax museum fire. True to its name, Decasia swarms with decay, a decay so frenzied it is, paradoxically, lively.

Still from Decasia: The State of Decay (Bill Morrison, 2002). Courtesy Decasia website.

In his New York Times Magazine article about Morrison’s movie, Lawrence Weschler describes the slow-motion decomposition “afflicting virtually all nitrate film stock (and nitrate film stock was the medium for most filmmaking until the 1950’s). Because it is chemically unstable, cellulose nitrate film stock begins decomposing the moment it is manufactured, a process that accelerates with the passage of time.” The luminous, silver images borne of nitrate become discolored, the emulsion turns sticky, “exuding a brown frothing foam (known to conservators, quaintly, as honey)” and, ultimately, hardens into a brittle mass, then crumbles into a reddish powder, so combustible it has been known to burst spontaneously into flame. No one will ever see Greta Garbo in Divine Woman or Thea Bara in Cleopatra again; both films, along with more than half of the 21,000 feature films produced before 1950, are presumed lost. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

Still from Decasia: The State of Decay (Bill Morrison, 2002). Courtesy Decasia website.

Which makes poetic sense, given that filmic images are by their very nature scenic postcards from the afterlife, home movies of the living dead. Photography is about suspended animation, the living flash-frozen in mid-breath; cinema is about reanimation. Photography is painless taxidermy, performed on the living; the movies are a branch of necromancy. Photography traps the soul behind those unblinking eyes that meet our gaze or, even more uncannily, follow us around the room. Hence the morbidity of the daguerreotype, an open-casket creepiness exploited to powerful effect in the gothic chiller The Others (Alejandro Amenábar, 2001). When a pair of precocious children stumble on a 19th century post-mortem photograph of their family’s domestics, they realize with a shudder that the servants are, in fact, ghosts. Of course, to the modern eye, the unsmiling, sepia-toned phantoms that stare fixedly out of Victorian photographs look as if they’re already dead; the daguerreotype simply dramatizes the fact that all photography is post-mortem photography.

A photograph can preserve its subject forever in an instant of horror, like the suspected Viet Cong terrorist being executed by a South Vietnamese police chief in Edward T. Adams’s famous photograph. Point-blank murder by a pistol bullet to the head is horrific enough, but if there is a fate worse than death, it is being sentenced to spend eternity imprisoned in the split second of your death. True, the V.C. whiplashing from the bullet’s impact is dead and gone, never to know the media half-life of his disembodied image, but we do, and therein lies his fate, the kinder, gentler cruelty of the media age.

“[P]hotographs actively promote nostalgia,” writes Susan Sontag, in On Photography. “Photography is an elegiac art, a twilight art. […] All photographs are memento mori.” Scratch the surface of nostalgia, and you’ll find a deep strain of necrophilia, just beneath the melancholia. The dream of stepping through the daguerreotype, into the past, is the dream of undeath, of traveling back to an embalmed time, where things move in slow motion, or not at all, forever freeze-framed.

Still from Decasia: The State of Decay (Bill Morrison, 2002). Courtesy Decasia website.

The nostalgia index tracks the anxieties of any age, and our age is more anxious than any decade in recent memory. “In counterpoint to our fascination with cyberspace and the virtual global village, there is a no less global epidemic of nostalgia, an affective yearning for a community with a collective memory, a longing for continuity in a fragmented world,” writes the cultural historian Svetlana Boym, in The Future of Nostalgia. “Nostalgia inevitably reappears as a defense mechanism in a time of accelerated rhythms of life and historical upheavals.” In the 21st century, the movie screens of the mass unconscious are haunted by nightly news images of jetliners jack-knifing through the Trade Towers, abject hostages begging not to be beheaded, cars exploding into oily fireballs in downtown Baghdad. Like the inhabitants of the doomed planet in the old Star Trek episide “All Our Yesterdays” (1969), who use a machine called the Atavachron to flee into the past, we seek solace in other times, any time but ours. Irony of ironies, our desperate insistence on clinging to lost moments is dragging the then and there into the here and now, overcrowding the present with spectral yesterdays.

—Mark Dery (© Mark Dery, 2005.)

Diane

Best article yet, and for me, fresh from two days of 5th grade graduation (5th grade mind you) pageantry complete w/ parents who don’t see anything if not through the lens of a camera – still or video, it was a very timely article. Plus, who doesn’t love the phrase ‘supperating wound?’

Those stills from the movie are beautiful.

Diane

Dominic

For the aural equivalent, see William Basinski’s “Disintegration Loops.”

http://www.pitchforkmedia.com/record-reviews/b/basinski_william/disintegration-loops.shtml

t o n x

Thanks for that link Dominic… I’ll check that out.

Enjoying your blog Mark. Keep up the great work.

M. Dery

Basinski sounds well worth a listen. I should have mentioned that the post-minimalist score for DECASIA is a pitch-perfect aural echo of the visual decay happening onscreen. It’s a *de*composition. (Forgive pun…) It consists mostly of Philip Glass-ian ostinati, but is much more harmonically pungent than Glass, and uses microtonality to evoke a sense of things crumbling to dust. In certain passages, the composer has half the orchestra playing a quarter-tone flat while the other half is playing a quarter-tone sharp, creating a sweet-sour, seasick effect that perfectly mirrors DECASIA’s lively corruption. Or something like that.

Jacob C.

Frank Zappa once theorized that nostalgia occurred in cycles, and that the eras we look back upon as “retro”-cool are gradually getting closer and closer to the present. You yourself, in the essay, cite the phrase “so five minutes ago” as an example of our obsession with moving forward at all costs, or at least that’s how I interpreted it; Zappa would see it as an instinctive need to outrace the stagnation of our own culture, which he saw (as you seem to do) drowning itself obsessively in its own past.

FZ even said it might get so bad that someday we won’t be able to take a step without feeling nostalgic for the last step we took; we’ll be paralyzed.

Nothing more to add; my apologies if none of it made sense.

M. Dery

“FZ even said it might get so bad that someday we won’t be able to take a step without feeling nostalgic for the last step we took.” Right. That’s what I call “nostalgia for the present” (a close cousin of Baudrillard’s “nostalgia for the real.”) Where did Zappa say this, do you recall?